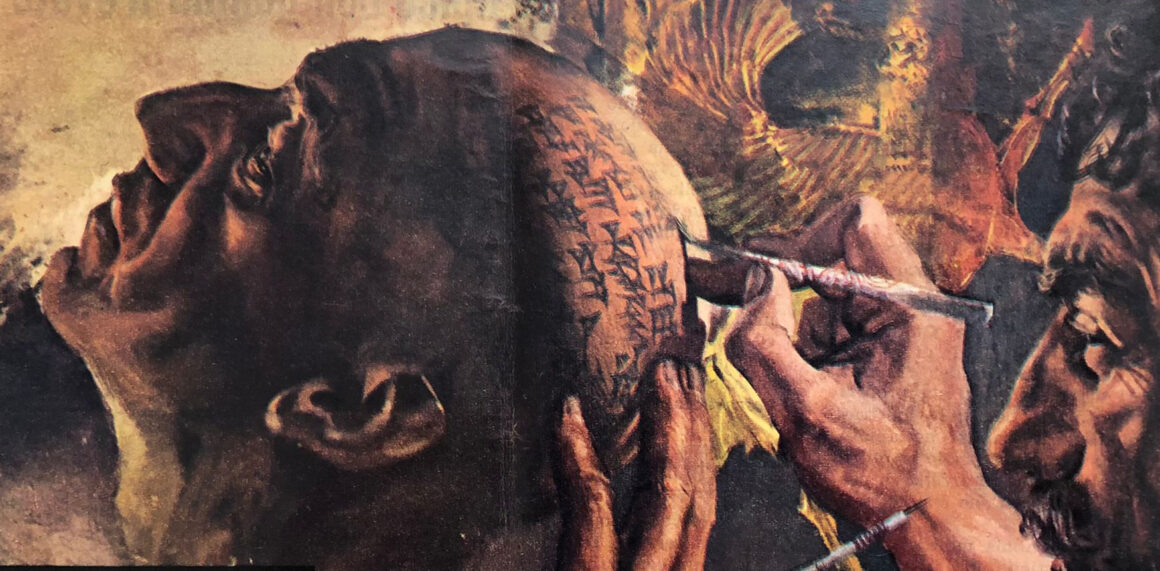

More than 24 centuries ago, a Greek ruler named Histiaeus needed to send a secret message to his ally, Aristagoras. A pigeon wasn’t going to cut it, so he got a little creative. He summoned his most loyal slave, shaved his head, and wrote the message on his scalp. After bandaging the slave’s head, Histiaeus waited until the hair grew back, then sent him on his way to deliver the message.

This unusual method of concealing a message is considered the first recorded use of steganography. From that point onward, our methods only grew more creative. As new forms of media emerged, the techniques for hiding messages in plain sight have evolved right alongside them.

Since then we have come a long way, from hiding messages on a literal man’s head to writing with invisible ink (thankfully on paper) or encapsulating the secret message in the first letter of every word, more generally known as null cipher

But what if you don’t have a slave to write on his head or can’t craft a seemingly innocent essay that perfectly fits the message in its correct place? Well you are in luck, since the age of computers, We don’t have to hide messages in physical items anymore, we can embed them in countless formats like images, videos, or sound files, in this article we will discuss how to hide a secret message subtly in any image.

As you probably know, most images consist of three channels, red, green and blue, and these values add up to give you some unique color, most images are also 8bit, meaning that every pixel in a channel has a value between 0 to 255. Having known that, let’s take a closer look at this samurai image and zoom all the way to this particular pixel

One of these squares is identical to our chosen pixel above and the other one i have altered its red channel by one, can you tell which is which?

I’m guessing here that you don’t have superpowers and that you indeed can’t tell the difference, especially without the zoom in, so we can actually leverage this to to easily embed a secret message in any digital image without raising suspicions by modifying the pixels ever so slightly, probably….

Disclaimer: changing the values of pixels can change the image’s statistical distributions, so if the change is big enough and/or an analyst is clever enough, it can be detected

As we mentioned earlier, all pixels range from 0 to 255 and this can be represented by 8 bits in binary system, so we can modify the least significant bit and all that will happen is an imperceptible change by one

Now enough chit chatting and let’s fire up an interpreter.

First things first, let’s get our tools set up

we will need opencv to process images, and textwrap because i hate for loops

import cv2

import textwrap

let’s set up the message that we want to send, i like this quote so let’s use it

msg = "By believing passionately in something that still does not exist, we create it."

To embed text into images, we first need to convert the text into ASCII character encoding, and then translate it into its binary representation. Each ASCII character is represented as a byte, for example the letter M is 77 in decimal or 01001101 in binary

The ord() function retrieves the ASCII value of each character as an integer, while the format() function converts this integer into its binary form. We use the format specifier ‘08b’, which ensures that the binary string is always 8 bits long by padding with leading zeros if necessary.

Here’s a Python function that performs this conversion:

def ascii_to_binary(s):

return ''.join(format(ord(char), '08b') for char in s)

binary_msg = ascii_to_binary(msg)

binary_msg

[output]:

'01000010011110010010000001100010011001010110110001101001011001010111011001101001011011100110011100100000011100000110000101110011011100110110100101101111011011100110000101110100011001010110110001111001001000000110100101101110001000000111001101101111011011010110010101110100011010000110100101101110011001110010000001110100011010000110000101110100001000000111001101110100011010010110110001101100001000000110010001101111011001010111001100100000011011100110111101110100001000000110010101111000011010010111001101110100001011000010000001110111011001010010000001100011011100100110010101100001011101000110010100100000011010010111010000101110'

When decoding the image, we need to reverse the process by converting the binary back to ASCII. The textwrap.wrap() function splits the binary string into chunks of 8 bits, with each chunk representing one byte, which corresponds to an ASCII character. After converting these 8-bit chunks into integers, we can form a list of ASCII values, convert them into a bytes object, and finally decode it back to readable text.

Here’s the function that handles the conversion from binary to ASCII:

def binary_to_ascii(binary_msg):

bytes_list=[int(byte, 2) for byte in textwrap.wrap(binary_msg,8)]

ascii_msg=bytes(bytes_list).decode('ascii')

return ascii_msg

binary_to_ascii(binary_msg)

[output]:

'By believing passionately in something that still does not exist, we create it.'

As we mentioned before, the fundamental method for embedding the message involves replacing the least significant bit (LSB) of a pixel. Let’s create a function to abstract this process:

def replace_LSB(binary_str, new_bit):

return binary_str[:-1] + new_bit

replace_LSB('11111111','0')

[output]:

'11111110'

Next, we need a way to determine where the hidden message ends. Without a clear endpoint, we would have to assume the entire image contains the message, which could result in either errors or the display of meaningless text. To solve this, we’ll append a specific sequence of bits at the end of the message, which serves as a marker. During decoding, we’ll search for this pattern to identify the end of the message.

In this case, we’ll use the binary representation of the ASCII sequence ‘\eom’ (End of Message) as our marker:

def get_eom_index(binary_msg,s=0):

'''find the end of message position'''

index=binary_msg.find(ascii_to_binary('\eom'),s)

if index!=-1:

return index

return False

This function searches for the binary pattern representing ‘\eom’ starting from position s. If the pattern is found, the function returns its index, marking the end of the message. Otherwise, it returns False, indicating that the end marker wasn’t found.

msg = "By believing passionately in something that still does not exist, we create it.\eom"

binary_msg = ascii_to_binary(msg)

get_eom_index(binary_msg)

[output]:

632

Now that we have all the necessary tools, let’s load an image and look up its dimensions.

img=cv2.imread('puppy.jpg')

height=img.shape[0]

width=img.shape[1]

print(img.shape)

[output]:

(1280, 1024, 3)

They say a picture is worth a thousand words, but I think we can do better! Let’s calculate exactly how much better.

The image we are working with is 1280x1024 and has three channels (RGB). This means we can theoretically store a message of up to 3,932,160 bits, which equals 491,520 bytes (or characters).this averages out with more than 82 thousand words, so it’s 82 times better!

Next, we’ll iterate over the pixels in the first channel of the image, read the pixel values, and convert them to binary. We’ll replace the least significant bit (LSB) of each pixel with a bit from our message. Once the LSB has been replaced, we’ll update the pixel’s value with the new integer representation. After embedding all the message bits, we’ll write the modified image back to disk.

i=0

j=0

for k, msg_bit in enumerate(binary_msg):

i=k//height # #rows

j=k%width #wrap around #cols

pixel_bin=bin(img[:, :, 0][i,j]) # pixel value in binary @ i,j

pixel_bin_encoded=replace_LSB(pixel_bin,msg_bit)

img[:, :, 0][i,j]=int(pixel_bin_encoded,2)

cv2.imwrite('x.png',img)

if you write the image as jpeg the message might get corrupted because it’s a lossy compression format. so make sure to write it as png

And we are done! now you can send the image to your friends and they can easily decode the secret message! Let’s see how

This can be done by reading the image and extracting the least significant bit (LSB) from each pixel’s binary value. As mentioned earlier, it’s inefficient to scan through the entire image, so instead, after every 64 bits, we’ll search the decoded binary message for the end-of-message (EOM) pattern. If we find it, we’ll stop scanning the image.

To optimize further, we won’t start searching from the beginning of the message after each read, as we already know that the EOM pattern wasn’t found in the last segment. This way, we only search from the point where we last left off plus some search window clearance because the pattern could be split between two segments

img_2=cv2.imread('x.png')

height=img_2.shape[0]

width=img_2.shape[1]

decoded_bin_msg=''

i=0

j=0

for k in range(width*height):

i=k//height # #rows

j=k%width #wrap around #cols

pixel_bin=bin(img_2[:, :, 0][i,j]) # pixel value in binary @ i,j

decoded_bin_msg+=pixel_bin[-1]

if k%64==0:

eom=get_eom_index(decoded_bin_msg,k-128)

print(k)

if eom:

break

decoded_bin_msg

[output]:

'010000100111100100100000011000100110010101101100011010010110010101110110011010010110111001100111001000000111000001100001011100110111001101101001011011110110111001100001011101000110010101101100011110010010000001101001011011100010000001110011011011110110110101100101011101000110100001101001011011100110011100100000011101000110100001100001011101000010000001110011011101000110100101101100011011000010000001100100011011110110010101110011001000000110111001101111011101000010000001100101011110000110100101110011011101000010110000100000011101110110010100100000011000110111001001100101011000010111010001100101001000000110100101110100001011100101110001100101011011110110110101010001111100111011111010011010111001101'

binary_to_ascii(decoded_bin_msg[:eom])

[output]:

'By believing passionately in something that still does not exist, we create it.'

We got our message back!!

To sum up, while steganography offers fascinating ways to hide messages in plain sight, it shouldn’t be your sole line of defense.It’s crucial to remember that steganography alone may not provide adequate security against determined adversaries. To enhance your message’s security, always pair steganography with robust encryption. By encrypting your messages before embedding them, you ensure that even if the hidden message is discovered, it remains unintelligible without the decryption key.